Revenge of the ROW

Monday | October 5, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Sun Spots.

DB here:

Watching Congress on C-SPAN makes you realize that the dead outnumber the living. Likewise, going to a film festival like Vancouver’s drives home to you how many movies there are out there. The world produces about 5000 features per year. No more than fifteen per cent of those come from the United States. That leaves about 4300 from what Hollywood execs apparently, and disparagingly, call ROW—the Rest Of the World. And hundreds of those 4300 are fighting for spots at the film festivals that have sprung up around the globe. Hence the rise of the programmer, today’s art-film gatekeeper and tastemaker.

To be a programmer you must be knowledgeable, traveled, and well-networked. You have to be steeped in contemporary film, you have to make your way to obscure places, and you have to know the right people—filmmakers, producers, sales agents, critics you can trust. Hence the power of a festival like Vancouver’s. It has superb programmers like Tony Rayns, Shelly Kraicer, Mark Peranson, Terry McEvoy, Stephanie Damgaard, Tom Charity, Sandy Gow, Tammy Bannister, and their colleagues.

You could mount a perfectly respectable event by cherry-picking other festivals’ lineups, but Vancouver mixes current international hits with genuine discoveries. Vancouver’s recognized specialties, like new Asian film, documentary, and Canadian features, nicely counterbalance their obligation to bring to the community the latest in top-drawer films of all sorts. A user-friendly festival in an exceptionally welcoming and picturesque city, Vancouver remains a magnet for us and hundreds of other cinephiles. This is my fifth visit, and Kristin and I commented online in 2006 (start here), 2007 (start here), and 2008 (start here).

This year’s Vancouver doesn’t lack big-name attractions. Keeping up their dedication to Manoel de Oliveira (a ripe 100-plus years old), the programmers have brought us Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, a sixty-minute package of pure pleasure. At first it seems a redo of Obscure Object of Desire. A man on a train recounts his frustrated efforts to marry a gorgeous young woman he glimpses at a window. But it turns out that this is an adaptation of a short story by Eça de Quieró, and things develop in very different directions than in Buñuel’s film. Oliveira’s characteristically chaste framings and sumptuous décor are enlivened by some errant formal devices that it would be a shame to divulge.

Okay, I’ll mention one because it kicks in from the start. On the train, Ricardo decides to tell his story to the woman sitting next to him. But while listening she usually looks straight into the camera. And every time she replies to his remarks, instead of turning to look at him, she delivers her lines directly to us. Ricardo looks at her, or sometimes just glances around as speakers do, but during her lines, the camera acts as a relay between her and him. You never quite get used to this strange displacement of dialogue, and it helps make Ricardo’s tale of archaic courtly love as subtly unnerving as the revelation that seals the couples’ fate. Whippersnapper directors a third Oliveira’s age would not dare so much.

Another much-awaited title was Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, and the hopes I expressed in the previous entry weren’t disappointed. A mentally handicapped boy is accused of murder, and his mother leaps into action to find the killer. As in Bong’s earlier Memories of Murder, a mystery intrigue ramifies into the lives of disparate characters, so that we’re skittering between physical clues (a golf club, inscribed golf balls, a strangely positioned corpse) and psychological ones, with bits of behavior serving to suggest multiple motives. Each character continues to surprise us—in particular, the sneering wastrel who takes advantage of the son. Driving the plot and passing through a spectrum of emotional changes, of course, is the title character. There’s no shortage of movies called Mother (though we’re told this one should properly be translated as Mother/Murder), but veteran actress Kim Hye-ja as the indefatigable guardian of her boy is as memorable as Pudovkin’s and Naruse’s protagonists.

Bong’s compact compositions are always at the service of his storytelling. I couldn’t see any fat on the scenes. His fluent pacing squeezes suspense and surprise out of each plot convolution. While the mother talks to her boy in jail, the lawyer stands at a distance from them, and, slightly out of focus, checks his watch. Instantly we know that he’s uninterested in the case. But Bong also knows how to linger. One of the most memorable slow dissolves I’ve seen in recent years counterposes mother and son, sleeping alongside each other off-center, against a horrific discovery tucked against the other edge of the anamorphic frame.

Mother has plot to spare; it could loan some to Sun Spots. What hath Hou wrought? I thought during the first few minutes of this exercise in Asian minimalism. This relentlessly dedramatized tale of a fugitive triad who meets a sulky girl in the countryside is determined to deny us any significant action, intense emotion, or old-fashioned enjoyment. Long shots, some very distant; thirty-one single-take scenes; impassive actors smoking, staring, turning from the camera, and generally hanging out: We have been here before. After twenty years of masterpieces by Hou, Kore-eda (Maboroshi), and Jia Zhangke (Platform), this style risks mannerism.

Eventually, though, I shifted gears and came to respect the movie. First, the landscapes are ravishing, worthy of a James Benning film. (8 ½ x 11, in which narrative gestures are swallowed up in immense spaces, wouldn’t be an irrelevant comparison.) Second, many compositions develop in unpredictable ways, and you’re given enough time to scan the frame for clues to what has happened before we join the scene. You’re obliged to notice handbags, cellphones, fishing poles, and cigarette butts strewn across the visual field. Third, director Yang Heng has exploited one powerful advantage of HD video: razor-sharp depth of field. This allows him to integrate distant hills and streams into the action. You see everything sharp and fresh, even actions hundreds of yards away. The final nine-minute shot forms a kind of climax of spatial acuity. A couple, trailed by a solitary figure, drift away from us into a grove of trees, and they remain visible as patches of white and black for an achingly long time before finally disappearing. Here “vanishing point” takes on its full meaning. Unthinkable on DVD, Sun Spots lives fully on the big screen, and one has to respect Yang’s single-minded commitment to making an anecdotal plot into something austere and sensuous.

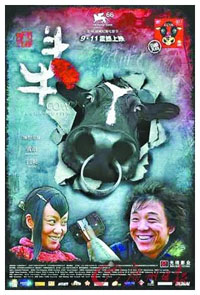

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Kristin and I have already seen plenty of other films we want to commend to you, but hitting four screenings a day hasn’t left us a lot of time to blog. Still, we’re determined to bring you more comments on this wondrous festival’s offerings.

Cow.